If you’re involved in drug discovery, you’ve probably heard someone say, “This compound has a great docking score so it must be a good inhibitor!” As someone who’s spent years in computational drug design, I cringe every time I hear this. Seriously, it’s just awful. Let’s dive into the truth about docking, what it can and can’t do.

Table of Contents

- What Is Molecular Docking?

- 4 Ways You Should Not Use Docking

- 2 Ways You Could Use Docking

- Best Practices For Using Docking In Drug Discovery

- Closing Remarks

- References And Further Reading

What Is Molecular Docking?

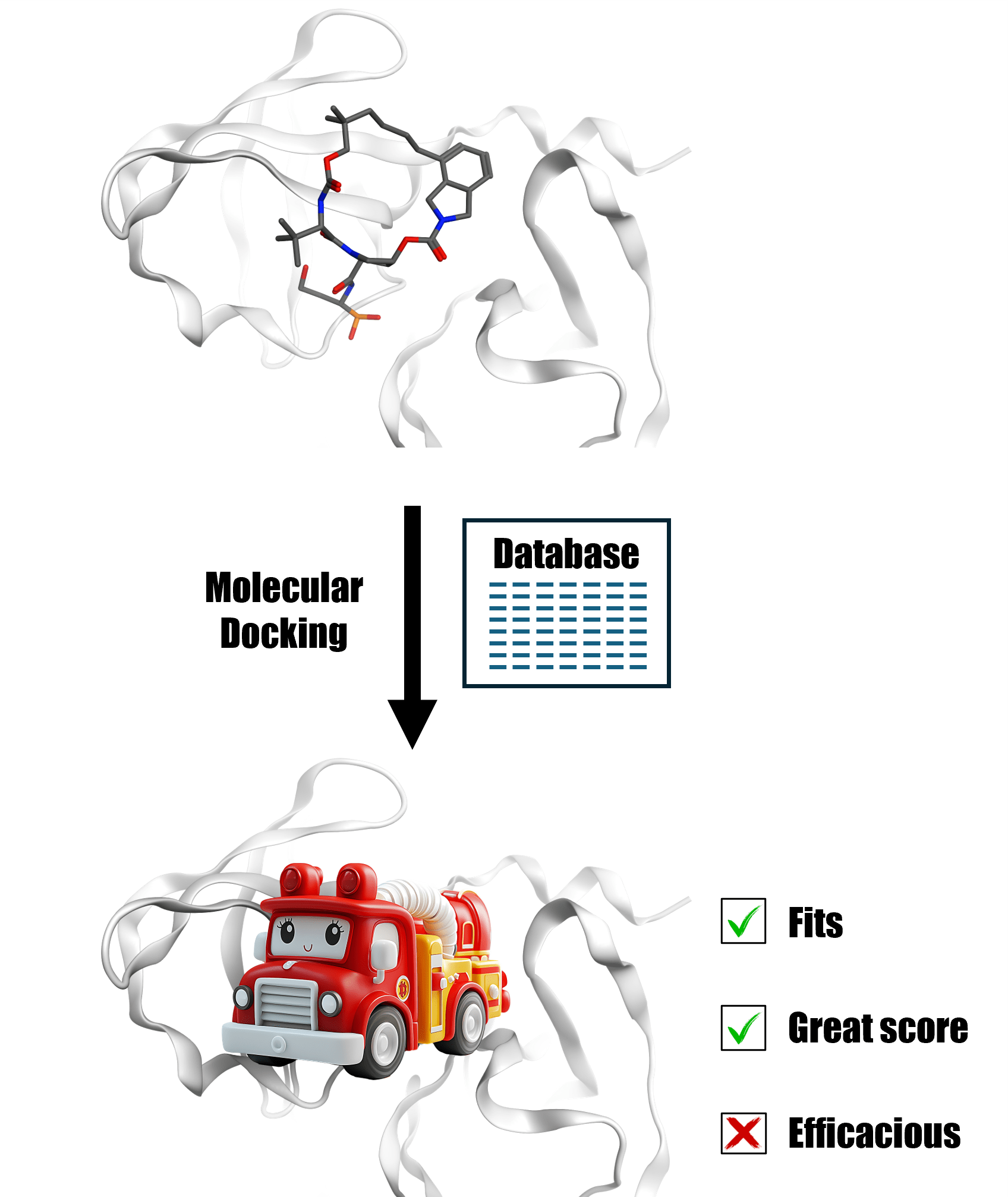

Before we jump into the dos and don’ts, let’s get on the same page. Molecular docking is a computational method used to predict how a small molecule (ligand) might bind to a target macromolecule (e.g. a protein or nucleic acid). These days, protein-protein structures can also be predicted. Docking is a prevalent technique used for hit identification and lead optimization, falling under the heading of structure-based drug design.

Docking Approaches

Docking relies on an algorithmic search to explore different ligand orientations within the binding site. Common approaches include:

- Rigid-body docking: Treats ligand and receptor as rigid structures.

- Flexible ligand docking: Allows ligand to adopt multiple conformations.

- Flexible receptor docking: Incorporates protein flexibility (induced fit).

Once ligand poses are generated, a scoring function is applied to estimate how well the ligand fits into the binding pocket, the so-called docking score.

Categories of Docking Scores [1]

- Force-field- or physics-based: Uses molecular mechanics potentials like electrostatics and van der Waals interactions. Possibly even QM.

- Empirical: Fits experimental binding data to a mathematical model weighted by linear regression. Relies on high-quality, internally consistent data.

- Knowledge-based: Derives potentials from statistical analysis of known complexes, favoring interatomic pairs that occur frequently.

- Descriptor- or ML-based: Uses descriptors and training sets to predict docking scores of a test set, like traditional QSAR.

Components of Docking Scores

- Electrostatic interactions

- Hydrophobic effects

- Shape complementarity

- Desolvation

Phew, that was a lot of background, and it really only grazes the surface. But it’s good enough for now. Let’s get into where things go pear-shaped.

Researchers commonly use docking to estimate binding modes and affinities. The process is based on the assumption that molecular recognition is driven by structural complementarity and energetics. This assumption sounds good to me. It contains simple and physically intuitive logic culminating from decades of biochemical research. Docking can be useful for generating hypotheses of binding modes. But here’s the thing: docking cannot predict binding affinities.

4 Ways You Should Not Use Docking

1. Predicting Absolute Binding Affinity

That -15 “kcal/mol” score looks enticing, doesn’t it? Don’t take the bait. Binding affinity depends on the entire free energy landscape, not just a single docking pose. Protein dynamics and conformational entropy are huge factors. Kinetics and residence time also influence binding affinity, but are not accounted for in docking.

This is not a novel concept. Many studies such as this one [2] have demonstrated that scoring functions can predict correct binding poses but fail to accurately rank compounds by binding affinity. I have seen this in my own work as well.

A search in Scifinder with the prompt “agreement between molecular docking score and binding affinity” turned up 2,890 journal articles from 2020-present (searched Feb. 12, 2025). I didn’t check the relevance of every single one of them, but many of them include boasted improvement from deep learning; perhaps not a surprise. We’ll have to wait and see how the field progresses.

2. Comparing Scores Across Different Proteins

Comparing a set of ligands across different proteins is an apples to oranges comparison. You may be able to get away with comparison among similar protein families, but use caution.

It is valid to compare a set of ligands to one protein target (traditional docking) or a single ligand to a set of protein targets (reverse docking).

3. Making Decisions On Synthesis

Choosing which molecules to advance to the next stage of experimentation is a nuanced decision that requires communication between a team of experts. A computational chemist is one of those experts.

Don’t present your list of compounds that you prioritized with docking or any other method as the gospel truth. Keep expectations realistic. On top of the issues with binding affinity we’ve discussed, docking (and my favorite method, too) doesn’t account for:

- synthetic accessibility

- metabolic liability

- pharmacokinetic properties

- off-target effects

4. Predicting/Explaining SAR

Subtle changes in structure can lead to dramatic changes in binding that docking just can’t capture. Oversimplifying water networks and incompletely accounting for induced fit dynamics are two reasons docking fails to predict structure-activity relationships.

2 Ways You Could Use Docking

Now that we’ve covered what not to do, let’s talk about where docking can be a useful tool in your repertoire.

1. Generating Binding Hypotheses

Docking excels at suggesting possible binding modes. This is especially true in de novo docking in the absence of a bound ligand or in binding site exploration. I suggest you try post-docking refinement with molecular dynamics and rescoring with MM-GBSA/MM-PBSA or even free energy perturbation if resources are available.

2. Virtual Screening Filter

If a molecule fits, it will give a great docking score. Conversely, if a molecule doesn’t fit due to clashing or other shape complementarity issues, the score will be poor. Intelligently setting this threshold value can help filter out false positives after a ligand-based virtual screening campaign. Side note: I would always start a virtual screening campaign with ligand-based tools if I have the option.

The above figure is an excerpt taken from a ligand-based virtual screening benchmark study I conducted using DUD-E. The query molecule scored well with the ligands of both targets shown, but only fit well in one pocket after docking.

Best Practices For Using Docking In Drug Discovery

1. Use Ensemble Docking

Consider multiple protein conformations to account for different regions of chemical space (more comprehensive than induced fit protocols).

One possible protocol for generating input protein structures for ensemble docking:

- run several MD simulations on the target protein (10 x 25 ns, for example)

- cluster trajectories according to binding site RMSD

- use centroid of cluster for docking

2. Combine Multiple Methods

Utilizing a multi-pronged approach is usually the way to go in discovery. Use ligand alignment first if known binders of your target exist. Then, cross-validate with docking and rescore with MD simulations. Integrate experimental data iteratively to constantly improve your models.

Closing Remarks

Remember: The goal of docking isn’t to perfectly predict binding affinity. At the end of the day, we want to use computational tools in the smartest way possible to guide drug discovery efforts in an expedient way. Use them wisely, validate your results, keep limitations and assumptions in mind, and communicate your results clearly.

Want to learn more about getting the most out of computational techniques? Check out my other posts, like this one on geometry optimization. Reach out to [email protected] to be added to my e-mail list.

Until Next Time,

Avery

References And Further Reading

- Liu, J.; Wang, R. “Classification of Current Scoring Functions.” J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 475–482. DOI: 10.1021/ci500731a.

- Warren, G. L., et al. “A Critical Assessment of Docking Programs and Scoring Functions.” J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5912-5931. DOI: 10.1021/jm050362n.

- Guedes, I. A., et al. “Empirical Scoring Functions for Structure-Based Virtual Screening: Applications, Critical Aspects, and Challenges.” Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1089. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01089.

- Crampon, K., et al. “Machine-learning methods for ligand–protein molecular docking.” Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 151-164. DOI: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.09.007.

- Yassir, M., et al. “Drug Repositioning via Graph Neural Networks: Identifying Novel JAK2 Inhibitors from FDA-Approved Drugs through Molecular Docking and Biological Validation.” Molecules 2024, 29, 1363. DOI: 10.3390/molecules29061363.

Please consider supporting my blog!